|

| Rev. Henry Ward Beecher in Liverpool |

WHEN the secession movement first assumed serious proportions in the South, the sympathy of England was with the secessionists. There were many reasons for this. The political control of England was in the hands of the English aristocracy. Feudal England had always looked with both suspicion and aversion on her democratic daughter. The strongest argument against feudalism was the unparalleled growth of democratic America. Commercial England saw in the republic across the sea a rival who would soon contest with the mother country her claim to commercial supremacy, and she was not unwilling to see that rival dismembered, and her own commercial supremacy thus secured to her.

For more than a quarter of a century England had seen the South aggressive and successful, the North timid and retreating. It was not strange that she believed the South brave, the North timid; and England admires pluck and despises cowardice. During the four months between the election and the inauguration of President Lincoln she had seen the secessionists united, purposeful, aggressive; she had seen the North divided, vacillating, frightened.

|

| Punch magazine in London ridicules American aggressiveness in the Trent Affair, 7 December 1861. |

The Southern States were the great cotton producing states of the world; England was the great cotton manufacturing community of the world: the prosperity of England, almost the life of many of her people, was dependent upon the cotton supply furnished by the Southern States, and therefore dependent upon breaking any kind of blockades and keeping open the Southern ports to commerce. As the result of the Civil War the cotton supply had shrunk by May 1, 1862, from 1.5 million bales to 500 thousand bales, of which less than 12 thousand bales had been received from America.

In political circles in Great Britain Mr. Lincoln was unknown, and Mr. Seward, his Secretary of State, who was known, and who was erroneously supposed to be the controlling spirit in the new administration, was viewed with great distrust. However, when the famous abolitionist, republican minister from Brooklyn, Rev. Henry Ward Beecher, visited Europe for vacation, Lincoln's administration informally and unofficially encouraged Beecher to do a series of speeches throughout the UK.

|

| Abraham Lincoln. Photo by Mathew Brady |

At first he refused the requests urged upon him to speak. There were special reasons why he should refuse. He was there simply as a private citizen, without any connection with the government or any authority to speak in its behalf. The rumor, afterward circulated, that he had been informally and unofficially deputed by the administration to go to England, and endeavor to create a sentiment favorable to the North, he explicitly denied. He went wholly on his own responsibility with no supporter except his own church.

To speak for America was sure to invite every species of insult and indignity from Confederate sympathizers, and was not sure to receive encouragement or support from the few sympathizers with the North. It was not even certain that the speaker's efforts would not be condemned by the administration as possibly well meaning but practically injurious efforts. Mr. Beecher was unfamiliar with the conditions of the public mind, and by no means confident of his ability to meet them.

Lincoln's administration assured the reverend that the commercial and aristocratic circles of Great Britain were eager to have Great Britain intervene; that it was of the utmost importance, in order to prevent the danger of intervention, to arouse and instruct the anti-slavery sentiment of England upon the issues of the war.

Their plea to Beecher was that his popularity in Great Britain could do more than any other man to fore stall and counteract their intervention in the South.

The argument pre vailed ; Mr. Beecher's refusal was changed to con sent , and arrangements were made for successive speeches at Manchester, Glasgow, Edinburgh, Liverpool, and London.

Beecher in Liverpool

October 16th, 1863

|

| Rev. Henry Ward Beecher in Liverpool |

There are two Dominant races in modern history—the Germanic and the Romanic. The Germanic races tend to personal liberty, to a sturdy individualism, to civil and to political liberty. The Romanic race tends to absolutism in Government; it is clanish; it loves chieftains, it develops a people that crave strong and showy Governments to support and plan for them. The Anglo-Saxon race belongs to the great German family, and is a fair exponent of its peculiarities.

The Anglo-Saxon carries self-government and self-development with her wherever she goes. She has popular GOVERNMENT and popular INDUSTRY. As a self-governing people, there are more effects of a generous civil liberty upon their good order, intelligence, and virtue, even more so compared to the amazing scope and power of their creative enterprises. The power to create riches is just as much a part of the Anglo-Saxon virtues as the power to create good order and social safety. The things required for prosperous labour, manufactures, and commerce are three. First liberty; second, liberty; third, liberty. (Hear, hear.) Though these are not merely the same liberty as I shall show you. First, there must be liberty to follow those laws of business, which experience has developed, without restrictions or governmental intrusions.

Business simply wants to be let alone. (Hear, hear.) Then, secondly, there must be liberty to distribute and exchange products of industry and market without burdensome tariffs, without imposts, and without vexations regulations. There must be these two liberties - liberty to create wealth, as the makers of it can best think according to the light and experience which business has given them; then liberty to distribute what they have created without unnecessary vexatious burdens. The comprehensive law of the ideal industrial condition of the world is free manufacture and free-trade.

Hear, bear: (a Voice “ The Morrill tariff.” Another voice : “ Monroe.”) I have said there were three elements of liberty. The third is the necessity of an intelligent and free race of customers. There must be freedom among producers; there must be freedom among the distributors; there must be freedom among the customers. It may not have occurred to you that it makes any difference what one's customers are, but it does in all regular and prolonged business. The condition of the customer determines how much he will buy, and determines what sort he will buy. Poor and ignorant people buy little and that of the poorest kind. The richest and the intelligent, having the more means to buy, buy the most, and always buy the best. Here then are the three liberties—liberty of the producer; liberty of the distributor; and liberty of the consumer.

|

| Cartoon Depicting the Monroe Doctrine |

Britain then, aside from moral considerations, has a direct commercial and pecuniary interest in the liberty, civilization, and wealth of every people and every nation on the globe. (Loud applause.)

Both the worker and the merchant are profited by having purchasers that demand quality, variety and quantity. Now, if this is true in the town or the city, it can only be so because it is a law. This is the specific development of a general or universal law, and therefore we should expect to find it as true of a nation as of a city like Liverpool. I know it is so, and you know that it is true for the entire world; and it is just as important to have customers educated, intelligent, moral, and rich out of Liverpool as it is in Liverpool. (Applause.)A woman comes to market and says, “I have a pair of hands,” and she obtains the lowest wages. Another woman comes and says, “I have something more than a pair of hands; I have truth and fidelity"; she gets a higher price. Another woman comes and says, “I have something more; I have hands, and strength, and fidelity, and skill." She gets more than either of the others. The next woman comes and says, “I have got hands, and strength, and skill, and fidelity; but my hands: work more than that. They know how to create things for the fancy, for the affections, for the moral sentiments;” and she gets more than either of the others. The last woman comes and says, "I have all these qualities, and have them so highly that it is a peculiar genius;” and genius carries the whole market and gets the highest price. (Loud applause.)

Wherever a nation that is crushed, cramped, degraded under despotism is struggling to be free, you, the town of Leeds, Sheffield, Manchester, Paisley, all have an interest that that nation should be free. What is Great Britain's chief want?

They have said that your chief wants cotton. I deny it. Your chief want is consumers. (Applause and hisses.) You have got skill, you have got capital, and you have got machinery enough to manufacture goods for the whole population of the globe. You could turn out four-fold as much as you do, if you only had the market to sell in.

There are no more continents to be discovered. (Hear, hear.) How must the market of the future must be found?

|

| Rev. Henry Ward Beecher |

You must civilize the world in order to make a better class of purchasers. (Interruption.) If you were to press Italy down again under the feet of despotism, Italy, discouraged, could draw but very few supplies from you. But give her liberty, kindle schools throughout her valleys, spur her industry, make treaties with her by which she can exchange her wine, and her oil, and her silk for your manufactured goods; and for every effort that you make in that direction there will come back profit to you by increased traffic with her. (Loud applause.) every free nation, every civilized people, every people that rises from barbarism to industry and intelligence, becomes a better customer.

If the South should be rendered independent—(at this juncture mingled cheering and hisses became immense ; half the audience rose to their feet, waving hats and handkerchiefs, and in every part of the hall there was the greatest commotion and uproar.)

You have had your turn now; now let me have mine again (Loud applause and laughter.) after all, if you will just keep good nature, then I will not lose my temper; will you watch yours? (Applause.) Besides all that, it rests me and gives me a chance to catch my breath. (Applause and hisses.)

I think that the bark of those men is worse than their bite. They do not mean any harm. They don't know any better. (Loud laughter, applause, hisses, and continued uproar.)

I was saying, when these responses broke in, that it was worth our while to consider both alternatives.

Never have they for a moment given up the plan of spreading the American institutions, as they call them, straight through towards the West, until the slave, who has washed his feet in the Atlantic, shall be carried to wash them in the Pacific. (Cries of "Question,” and uproar.)

There! I have got that statement out, and you cannot put it back. (Laughter and applause.)

|

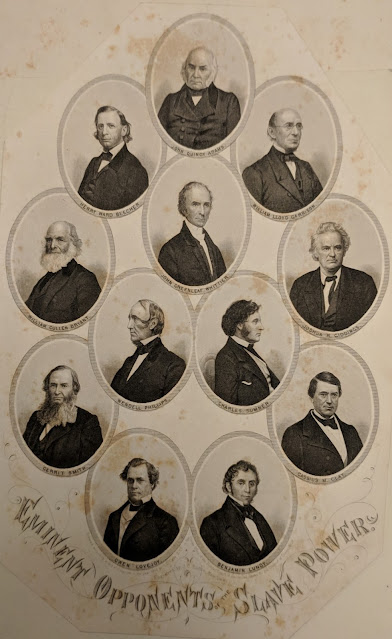

| Eminent Opponents of the Slave Power |

Now, let us consider the prospect. If the South becomes a slave empire, what relation will it have to you as a customer? (A Voice : “Or any other man.” Laughter.) It would be an empire of 12,000,000 people. Now, 8,000,000 are white and 4,000,000 black. (A Voice : “How many have you got? (Applause and laughter. Another Voice : “Free your own slaves.") Consider that one-third of the whole are the miserably poor, non-buying blacks. (Cries of “ No, no," “ Yes, yes,” and - interruption.) You do not manufacture much for them. (Hisses, "Oh!""No.") You have not got machinery coarse enough. (Laughter, and “No.”) Your labour is too skilled by far to manufacture bagging and linsey-woolsey.

(A Southerner : “We are going to free them every one.”) Then you and I agree exactly. (Laughter.) One other third consists of a poor, unskilled, degraded white population; and the remaining one-third, which is a large allowance, we will say, intelligent and rich here are twelve million people, and only one-third of them are customers that can afford to buy the kind of goods that you bring to market. (Interruption and uproar.)

My friends, I saw a man once, who was a little late at a railway station, chase an express train. He did not catch it. (Laughter.) If you are going to stop this meeting, you have got to stop it before I speak; for after I have got the things out, you may chase as long as you please but you would not catch them. (Laughter and interruption.) But there is luck in leisure; I'm going to take it easy. (Laughter.)

Two-thirds of the population of the Southern States today are non-purchasers of English goods. (A Voice : “No, they are not;" "No, no,” and uproar.) Now you must recollect another fact-namely, that this is going on clear through to the Pacific Ocean; and if by sympathy or help you establish a slave empire, you sagacious Britons—(“Oh, oh,” and hooting)—if you like it better, then, I will leave the adjective out-(laughter, hear, and applause)--are busy in favouring the establishment of an empire from ocean to ocean that should have fewest customers and the largest non-buying population. (Applause, “No, no.” A Voice : “I think it was the happy people that populated fastest.")

|

| Punch Magazine, November 8, 1856 |